When you're building a startup, few decisions matter more than how you choose to fund your growth. The capital you raise, and how you raise it, will shape your company’s trajectory, ownership stake, and eventual returns. Yet many founders still approach this decision with a one-size-fits-all mindset, defaulting to equity financing without understanding the alternatives or their implications.

The truth is that there’s no single answer. Debt and equity financing each have their place in a startup’s journey. The right choice depends on where you are, where you’re going, and what you’re willing to trade to get there. Here’s how to think about that choice, and what the data suggests.

What happens when you fund your startup through equity?

Equity financing is the path most founders think of when they hear startup funding. You exchange shares of your company for capital, bringing on investors who become partial owners of the business.

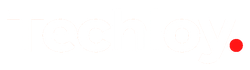

But the data behind equity financing tells a sobering story. According to Carta’s 2024 report, median dilution across funding stages leaves a typical startup with only about 40% of its shares remaining after a Series D round. What starts as complete ownership often ends with less than half of your company still in your control.

The dilution happens gradually, but the cumulative effect is significant. Each round chips away at ownership, and while your slice of the pie gets smaller, you’re betting that the pie itself grows large enough to offset the loss.

Despite that trade-off, equity investors often bring more than just money. The right partners can provide expertise, networks, and credibility. They can open doors to customers, partners, or other investors, and guide you through challenges they’ve seen before.

Equity also frees you from repayment pressure. There are no monthly interest payments or maturity dates. But that freedom comes at a cost beyond ownership percentage. Investors typically want board seats, voting rights, and influence over major decisions. Once you raise equity, you’re no longer making choices independently.

Is debt financing better if you want to keep control of your startup?

Debt financing works differently than equity. Here, you borrow money that must be repaid with interest, but you don’t give up ownership. For founders who value control or have strong cash flow, debt can be an attractive option.

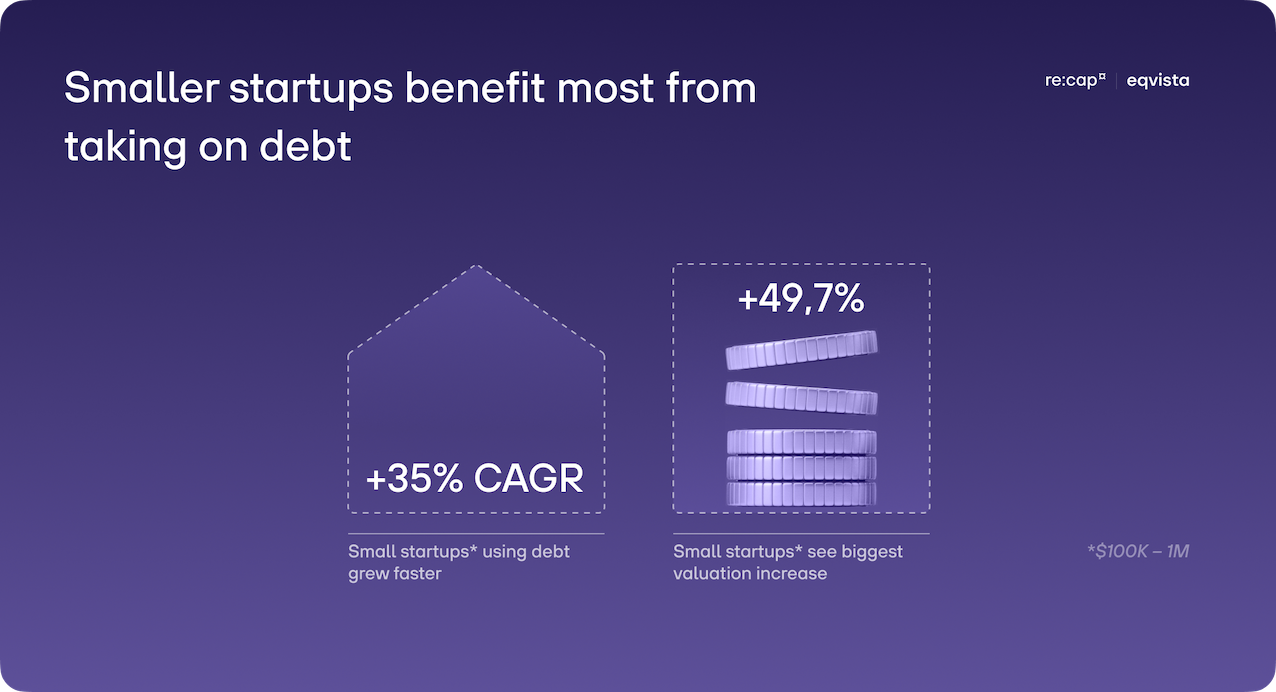

The economic case for debt can also be compelling. Startups that use debt financing have demonstrated higher revenue multiples, up to 49.7% more than their equity-only counterparts, according to Recap. The theory is that the discipline of making debt payments forces startups to prioritize revenue and operational efficiency early on.

Even from a cost perspective, debt is often cheaper than equity when you look at the long-term cost of capital. Interest might run at 10 to 15% annually, but the implicit cost of equity, the ownership you give up and the upside you lose, can be much higher. If your company eventually exits at a significant valuation, every percentage point of ownership you keep matters.

Debt financing also lets you maintain control. There are no new board seats or investor voting rights to negotiate. Your relationship with lenders is contractual, not ownership based. The catch is that debt requires consistent cash flow. Cash flow issues contribute to about 16% of startup failures, according to Victorflow. Taking on debt without reliable revenue can quickly make you part of that statistic.

Why the stage of your startup matters

One of the biggest mistakes founders make is treating the debt-versus-equity question as a binary choice. In reality, your ideal financing mix changes as your startup matures. The smartest founders use both, sometimes even at the same time.

In the early stage, when you’re validating your idea and searching for product-market fit, equity is usually the better option. You likely don’t have steady revenue to service debt, and you need flexibility to experiment. Seed and angel investors understand that they’re backing a vision more than financial performance.

Once you reach Series A and have early traction, debt becomes a useful tool to extend your runway between equity rounds. It lets you reach bigger milestones and command a higher valuation later. For example, if you borrow at 15% annual interest to gain six extra months of runway, and those months help increase your valuation by 30%, that debt dramatically reduces dilution.

By the time you reach Series B or beyond with proven revenue and a clear path to profitability, debt becomes an even more viable primary option. Why give away another 20% of your company if you can borrow what you need at a fraction of that cost?

Companies best suited for debt typically share similar traits: predictable revenue, recurring subscriptions, and clear payback periods. Software-as-a-service (SaaS) and other subscription-based businesses often fit this profile. If you can project revenue over the next six to twelve months, lenders are far more likely to work with you.

Conversely, startups with unpredictable income or long development cycles, like biotech firms awaiting FDA approval or hardware startups facing high manufacturing costs, are better off raising equity. When you’re still proving your business model, the flexibility of equity outweighs the pressure of debt.

Conclusion

There’s no universal answer to whether debt or equity is better for your startup. Anyone who says otherwise is oversimplifying a complex decision that depends on your stage, cash flow, business model, and long-term goals.

What’s clear is that both can play a role in a well-planned funding strategy. Equity provides patient capital, networks, and alignment for long-term growth, but it dilutes ownership and influence. Debt preserves control and can accelerate growth efficiently, but it adds repayment pressure and risk. The best founders understand when to trade ownership for partnership, and when to borrow just enough to stay in control of what they’ve built.