If you’ve watched popular series like Breaking Bad or The Big Bang Theory, chances are you’re already familiar with the idea of a spin-off. A side character that gets its own show, and what started as part of something bigger becomes a standalone project. That same idea ties into business, just with higher stakes and fewer cliffhangers.

What is a corporate spin-off?

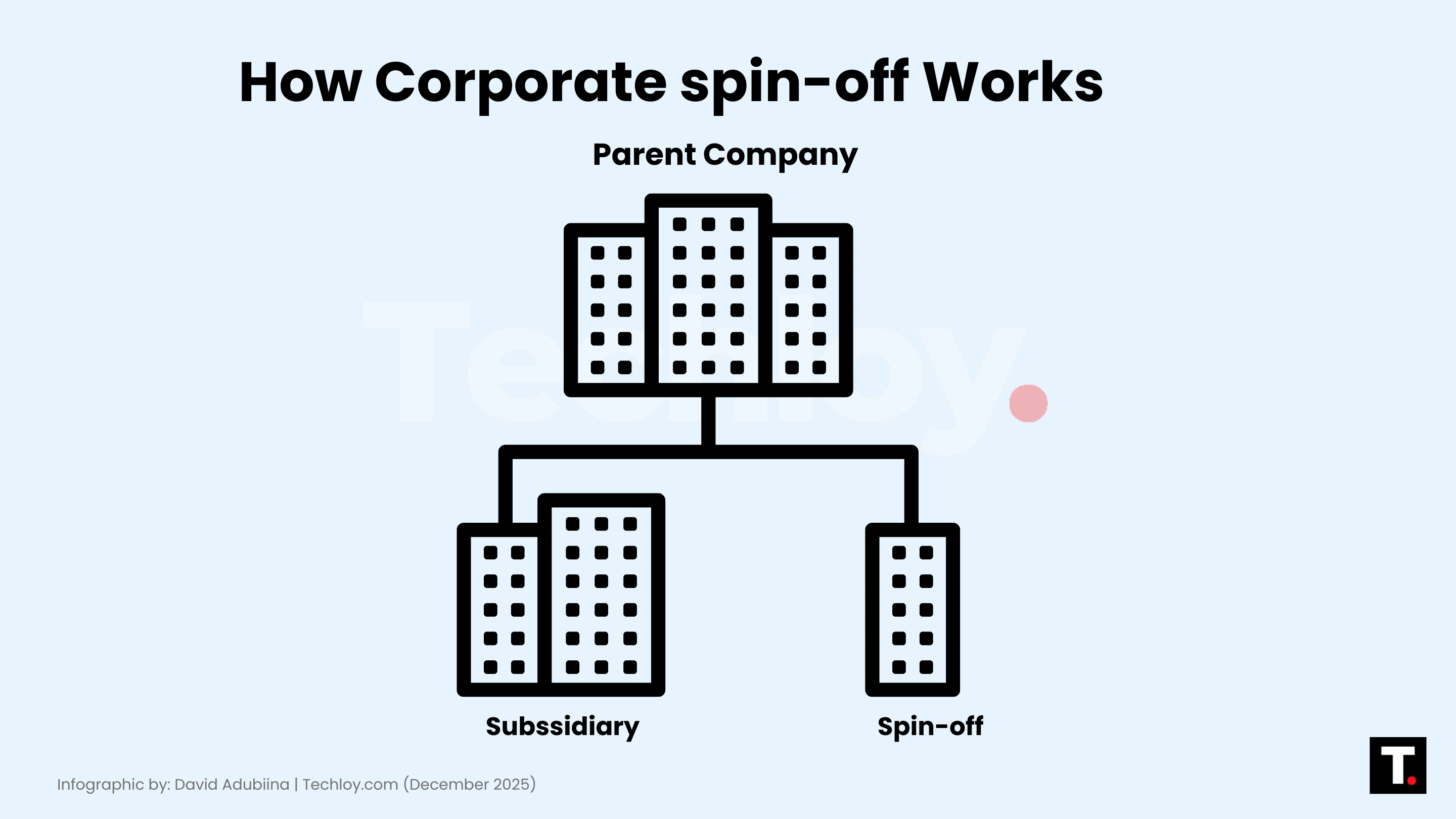

A corporate spin-off happens when a parent company takes one part of its business and turns it into a new, independent company. That division could be a product line, a subsidiary, or an entire business unit that no longer fits neatly into the parent company’s long-term plans.

Instead of selling it off, the parent company distributes shares of the new company to its existing shareholders. From that point on, both companies operate separately, with their own leadership and growth strategies. This allows each business to focus on what it does best, and in the process, the value that was buried inside a larger organization can finally surface.

In many cases, a spin-off is structured as a tax-free event for shareholders, taking several months to complete, and once it’s done, the spun-off company usually trades publicly on its own, standing apart from the parent company entirely.

Reasons for creating a corporate spin-off

There are several reasons a company might decide to split off part of its business into a separate, independent company. Most of the time, it comes down to focus, flexibility, and value.

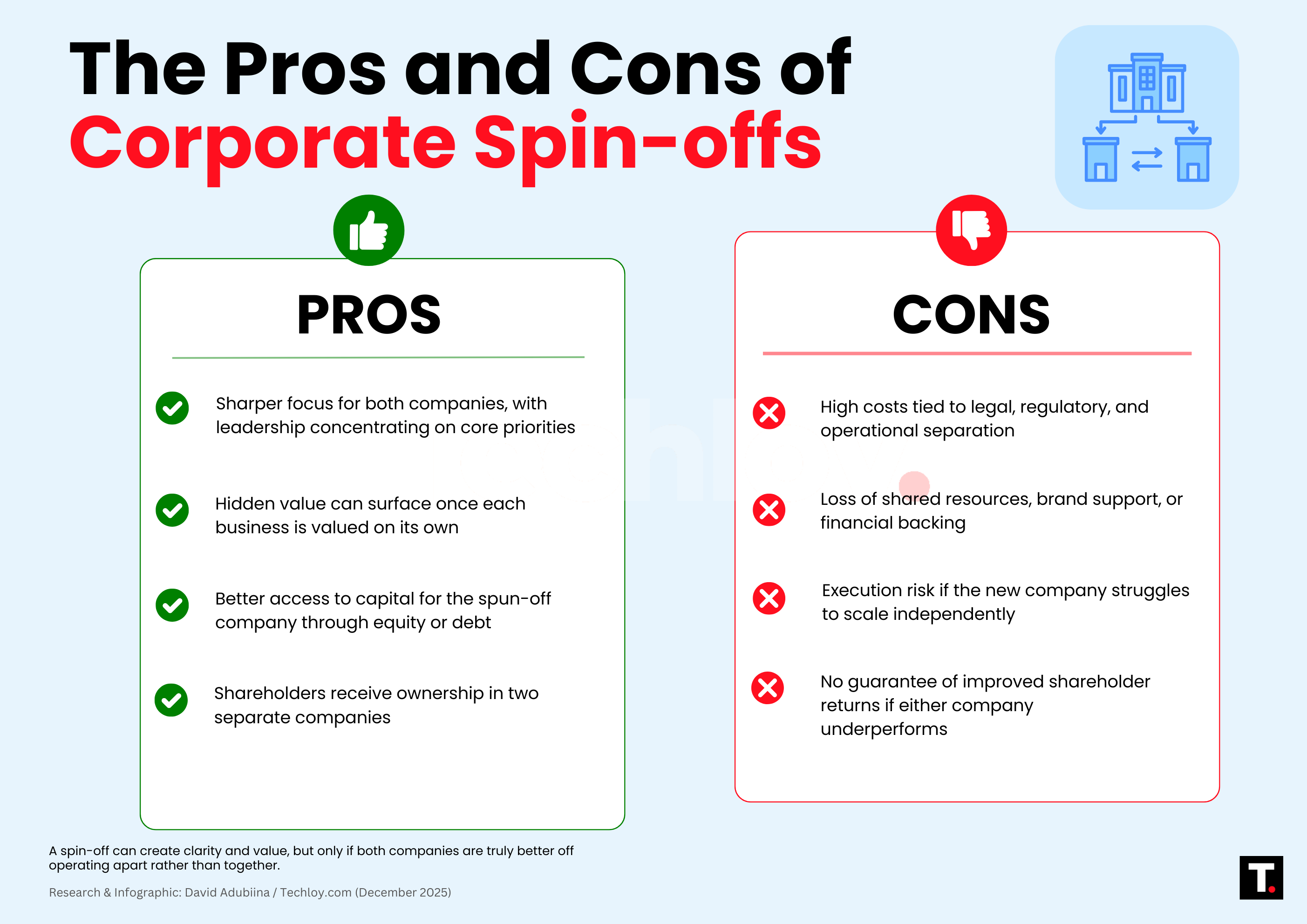

One common reason is to unlock value that’s buried inside the parent company. A division might be growing faster, slower, or simply differently from the rest of the business. When it's inside a larger company, that value can be hard for investors to see. Spinning it off allows the market to price it on its own terms.

A spin-off can also make it easier for the new company to raise capital. As a standalone business, it can issue its own shares or take on debt to fund growth. That kind of financing may not make sense, or even be possible, within a combined entity. Separation often makes the spun-off company more attractive to investors and lenders.

For the parent company, a spin-off creates breathing room. It allows leadership to focus on core operations without stretching resources across a division with different operational, marketing, financial, or talent needs.

In some cases, the division being spun off started as a supporting function, like a software or technology unit. Even if it’s profitable, it may not align with the parent company’s industry or long-term strategy. When business models start pulling in different directions, separation can make more sense than forcing everything under one roof.

Spin-offs can also happen when a division is underperforming. Creating a separate company removes the drag on the parent business and gives management more flexibility. The new entity can restructure, sell assets, or even explore a merger or acquisition without weighing down the original company.

How is it different from a corporate split-off?

At a glance, both spin-offs and split-offs might imply similar meaning, but the difference shows up in what shareholders are required to do.

In a spin-off, shareholders don’t have to make any decisions. If you own shares in the parent company, you automatically receive shares in the new company as well, usually in proportion to what you already own. After that, both companies trade separately, and shareholders end up holding stock in both.

A split-off works differently. Shareholders are given a choice. Instead of automatically receiving shares in the new company, they’re asked to exchange some or all of their parent company shares for shares in the subsidiary. You either keep the parent company, move into the new company, or rebalance between the two.

Because of this structure, split-offs are often used to clean up balance sheets, reduce parent company debt, or sharpen focus around a core business. The key distinction is simple: spin-offs are passive, shareholders get both companies, while split-offs are active, shareholders have to choose which company they want to own.

Examples of corporate spin-offs

One of the most well-known corporate spin-offs is PayPal’s separation from eBay. After acquiring PayPal in 2002, eBay ran the payments business as part of its broader commerce ecosystem for over a decade. In July 2015, eBay spun PayPal off into an independent, publicly traded company, with PayPal relisting on the Nasdaq shortly after the separation. The move gave both companies room to focus. eBay doubled down on online marketplaces, while PayPal pursued payments, fintech partnerships, and its own growth strategy.

Another high-profile example is Ferrari’s spin-off from Fiat Chrysler Automobiles. The plan was announced in 2014, with an IPO following in late 2015. By January 3, 2016, Ferrari officially became a standalone, publicly traded company, after FCA distributed its remaining stake to shareholders. The separation was designed to unlock Ferrari’s value and give the brand more flexibility to fund growth, with shares trading on both the New York Stock Exchange and Borsa Italiana.

Pros and cons of corporate spin-offs

Conclusion

Whether to spin off part of a business or keep everything under one roof largely depends on how clear a company is about its long-term direction. Not every division is meant to grow at the same pace or serve the same strategic purpose, and forcing that alignment can sometimes do more harm than good.

When a spin-off is done for the right reasons, it can unlock value and give both companies room to grow on their own terms. But it’s not a guaranteed win. The process demands careful planning, strong leadership, and a clear understanding of what each company looks like after the separation.

Essentially, spinning off a company only makes sense when independence creates more clarity and opportunity than staying together ever would.